Behavioral Health

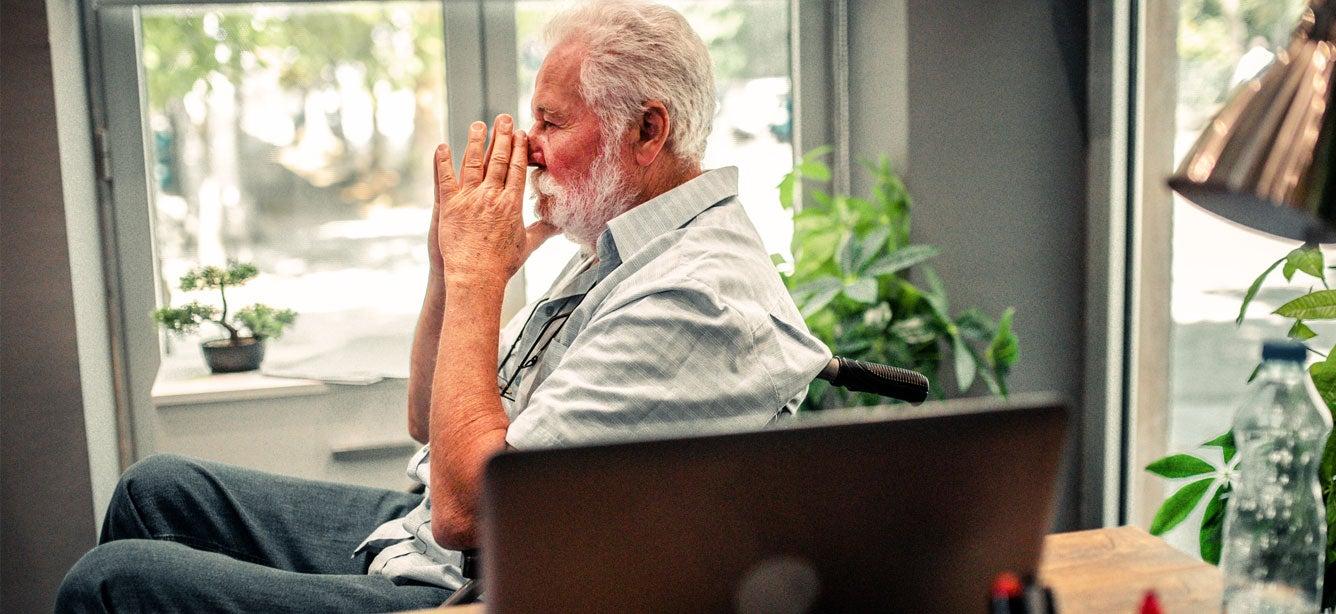

Getting the Care You Need via Telemedicine

Get the Facts on Healthy Aging

What Is Substance Abuse?

Help from the 988 Lifeline

There are caring people who want to help you, no matter what problems you’re dealing with. If you or an older adult you care about is struggling, dial or text 988 now to speak with a Lifeline counselor.